Brian Cook thinks so, but I’m not so sure. The idea that the spread, or, even just Gus Malzahn’s offense in particular, “is a modern-day version of the single wing” is overdone. (To be fair, the Judy Battista’s NY Times piece focuses on the wildcat, which I do think has a great deal in common with the single-wing.)

But Cook’s point is broader and, I think, flawed. He gives several reasons why Malzahn’s O in particular is like the single-wing, saying the single-wing

- incorporates many possible different ball carriers that head in different directions.

- uses misdirection as the primary way to acquire big plays. It’s not “keeping the defense honest” so you can run your bread and butter without the opponent cheating, it’s an attempt make the defense confused on every play.

- often features a primary ball handler who spins wildly to set up playfakes heading in opposite directions.

- depends on sowing confusion and can be vulnerable to teams that are well-drilled at stopping it.

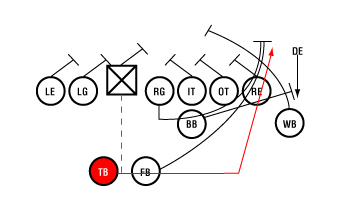

These reasons assuredly apply to Malzahn’s offense, but do they apply to the single-wing? Not really, or at least they aren’t its foundation. The single wing was primarily (though not always, of course) about using overwhelming force to one side of a formation. So the spread’s major similarity to the single-wing is mostly relegated to the shotgun and the fact that the quarterback is not an irrelevant handoff man, but instead has an active role in the run game. (H/t for the image FootballBabble.)

And the rest of Brian’s points don’t seem to apply. The single-wing was not a big play offense (have you seen the scores from back then?), instead relying on steady gains from its power runs. Indeed, most plays resembled rugby scrums, which made sense given football’s original roots. Some single-wing teams used a lot of ballcarriers — and I guess everything uses “a lot of ballcarriers” if the comparison is a Woody/Bo I-formation offense where one guy gets 35 carries a game — but it wasn’t a major feature. Playfaking was important but no more so than in other offenses, and certainly not as much as it is to offenses like the Wing-T. (And I don’t know about the single-wing being known for fakes involving “spinning wildly,” though various forms of the “spin” offense were invented decades later). And, although defensive discipline is helpful against any offense, the cornerstone of the single wing was the “student body right” type play behind the unbalanced line and blocking backs to the “single wing” side. There’s no misdirection to be snuffed out by a disciplined defense there; it’s called bowl your opponent over to get four yards. Below is video of an older school single-wing; I think it’s evident that it’s a little more straightforward than Brian’s four points would imply.

The upshot is that yes, the single-wing was a shotgun formation, yes it used some misdirection (all offenses do), and yes it’s old, but that doesn’t make it the sole inspiration for today’s spread or even Malzahn’s offense. Modern fans, including Brian, have understandably mapped their understanding of the offenses they see on a weekly basis onto the past and see a direct correlation, but it’s not quite that straightforward. Certainly, the coaches who developed today’s modern offenses, like Rodriguez and Malzahn, did not spend their time meticulously studying the single-wing tapes of yesteryear. Instead, if there are similarities it’s because those coaches stumbled onto the same ideas through trial and error.

So where did the spread come from? The basic answer is simple, though to catalogue all the influences would go on for days: the spread is a synthesis of most of the great ideas that came before it. It owes some principles to the single-wing, but it also owes its debts to the double-wing, a few Wing-T principles, the veer option squads, the run and shoot, and modern pro-style passing attacks. This makes sense, given that defenses, once they have countered something, do not forget, though at the same time an offense’s effectiveness is often contingent on how experienced the opponent’s coaches and players are to facing it. The “spread,” which is an overbroad term anyway, puts a new twist on a lot of what came before it.

But to say it is confined to being the “modern day version” of any one of those past offenses ignores too much football history to be a plausible interpretation. Like much football commentary, the analysis isn’t wrong, it’s just incomplete.